This is a written version of the talk that I gave in Stuttgart on Nov 12th for the “Resource Efficiency and Circular Economy Congress". It is not a transcription of my speech, but a version written from memory that maintains the gist of what I said

Ladies and gentlemen, first of all I would like to thank the organizers of this meeting because it is a pleasure and a honor to be here today. It is a pleasure, mainly, to see that the government of Baden-Wurttemberg is taking seriously the problem of mineral depletion and its environmental consequences, and that so much high quality work is being done on this subject here.

This said, I have 20 minutes to tell you how we stand in terms of worldwide mining trends. As you may imagine, it is not an easy task. The world's mineral industry is an unbelievably huge machine that extracts all kinds of minerals and processes billions of tons of materials. If we look at the data of the United States Geological service, the USGS, we find a listing of about 90 mineral commodities; but each commodity includes several varieties of the same, or related, compounds. So, it is really a complicated story to tell.

Nevertheless, myself and 16 coworkers set up to try to analyze the situation with a book that we titled "Plundering the Planet". It is a study that was sponsored by the Club of Rome. It is, actually, the 33rd report to the Club. Here is the cover of the book we published on this subject:

Of course, this study doesn't claim to be a complete survey of what's being done in the world's mineral industry, otherwise we would have had to put together an encyclopedia in 24 volumes or more. But I think that at least we were able to catch the main trends and, here, I can summarize the main results for you.

So, where do we stand in terms of mining? Or, asking the question explicitly: are we going to run out of something? And, if so, when?

At this point, the typical answer that you can find on the web or in most studies on the subject is a list of the available reserves of this or that mineral. Allow me to tell you that once you enter in this kind of evaluation, you enter a true minefield. The concept of "reserve" is a curious beast, a sort of chameleon that changes color depending on where it stands. Reserves are, by definition, mineral deposits that can be extracted, but what will actually be extracted depends on what you need and on what you can afford. As you may imagine, these concepts vary a lot with the vagaries of the economy. Then, there is another problem: the data about reserves are often proprietary and, in most cases, producers' assets are more valuable if they can list more reserves in their portfolio. That doesn't mean that the data are fraudulent but in the past some producers have been caught at, let's say, "inflating" a bit their resources. So, if you want to estimate for how long a certain mineral resource will be extracted at reasonable costs - which is what we are interested in - well, doing that is a difficult matter. It is an activity notoriously prone to mistakes; even large ones.

So, let me take a different view of the situation. I'll not be listing reserves, here, but I'll show you mainly historical production data and price trends. From that, we'll see if we can say something about the future.

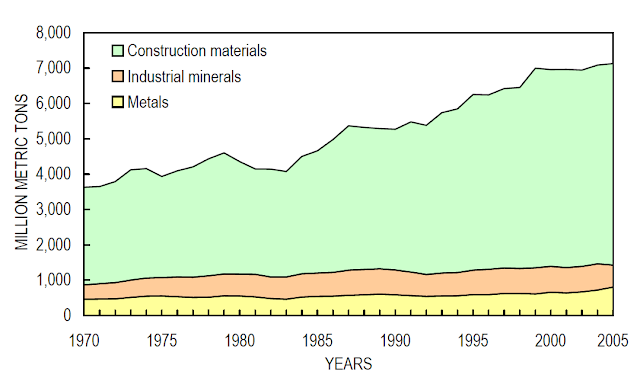

First of all, where do we stand in terms of overall mineral production? Let me show you the most recent aggregated data available, from USGS.

(Rogich, D.G., and Matos, G.R., 2008, The global flows of metals and minerals: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008–1355, 11 p., available only online at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1355/.

This image comes from a 2008 paper and is updated to 2005. From then, the trends haven't changed much. As you see, we are still growing in terms of total amounts produced. We have been moving billions of tons of materials during the past century and we are continuing to do so. In particular, construction materials, for instance cement, keep growing: it is a nearly exponential trend that shows no sign of abating. But, we can't live of cement, alone and I think you are more interested in the trends relative to fossil fuels - surely crucial for not just for the economy, but for our physical survival. So, let me show you some recent data.

Clearly, we don't seem to be running out of fossil fuels, at least as long as we measure production in terms of tonnage (Mtoe stands for "million tons of oil equivalent"). But note some trends: natural gas, and especially coal, are both rapidly growing - this is a bad thing, especially for coal, because coal's emissions of greenhouse gases are the largest of the three for the same amount of energy produced. Even natural gas, which is sometimes touted as a "clean" (or even "green") fuel also emits greenhouse gases and the problem of methane losses during extraction may make it as polluting as coal.

Notice also how the production of crude oil has been basically static during the past 7-8 years. That's important because crude oil is a crucial commodity for our transportation system and the fact that it has not been growing is telling us something. You have surely heard of the "new oil" story and how new technologies have revolutionized oil production giving to us a new age of abundance. Well, from these data it seems that, at best, these technologies have been able to avoid decline; not more. One reason is because these technologies have been used only in the United States; maybe they'll spread. But it is also true that after the great boom of "fracking" of the past few years, there are already signs of impending decline in the US. In any case, there is a general point that we should remember and that should dampen a bit the enthusiasm about new extractive technologies: the faster you extract it, the faster you run out of it.

There are further problems that this aggregated figure hides. One is that we should consider not just the total oil produced, but the oil produced per person. Here it is, in a graphic courtesy of Jean Laherrere.

You see, here, that if we consider the increase in population, the actual availability of crude oil per person has been declining after a peak that was reached in the early 1970s. It was the time of the great oil crisis that, apparently, never truly ended.

And you should also consider that, in Europe, we are all consumers of oil, not producers, so what we are interesting in is not really how much oil is produced in total, but how much oil we can import from producing countries. That depends, of course, on their internal consumption. Here, I could show you some data which indicate that several producers have big problems with their internal consumption increasing and that makes difficult for them not just increasing their oil exports but even in exporting any oil. But let me not go into the details.

These data show you that we are not running out of fossil fuels, not at all, but also that things are not easy. What's happening is that the industry needs to use more and more expensive technologies in order just to avoid a decline in production. And if we are spending more to produce oil, it means that prices must be rising; of course nobody ever would sell oil at a loss. So, here are the data for "Brent" oil, one of the industrial standards of oil.

Image by Ugo Bardi from EIA data

So, you can clearly see a rising trend here. It is not speculation. It is difficult to think that someone could speculate on a market of several trillion dollars per year but, even it they could, speculation is usually short lived. Here, we have an increasing price trend that started with the turn of the century and it is still ongoing.

We can justify these prices considering actual data on how much extracting oil costs. This is a difficult evaluation, of course, but it appears that the most expensive oil on the market, the so-called "marginal barrel", doesn't cost less than about 80 dollars. It is so expensive because it comes from remote fields, it requires deep drilling, it is high viscosity oil, contaminated oil, all sorts of factors that contribute to high costs. These costs can be measured in terms of energy needed to lift, purify, refine, etc. You can print as much money as you want, but that won't help you in lifting oil out of the ground. For that, you need energy.

And, please, note another important point. The prices of oil (and its cost), at present do not include pollution costs. When you buy gasoline for your car, you are not paying for the costs of global warming. And I don't have to tell you that, as we are discovering in this moment, after the tragedy of the Philippines, these costs are very high and that someone has to pay for them - sooner or later. To clean up the mess we ourselves are creating, we need energy.

Now, there is an interesting conclusion, here. It is that if we want to keep production at these levels, we must accept these prices. Prices are an indicator that says that energy and material resources must be channeled to the oil industry in order to make it able to keep production at the present levels. If we want to reduce prices, then we must accept a reduced production. And if we'll see a reduction in oil prices in the near future (which seems to be the recent trend) we'll see also production going down. This is the situation: surely not one of abundance even though, as I said, we are not running out of oil.

There would be a lot more to say about fossil fuels, obviously, but let me stop here. As I said, my idea was to give you some general idea of how the world's mineral industry is performing, so let me give you another example: copper. Here are the productive trends.

Now, copper is another critical commodity for the world's industry and I think this figure provides some food for thought for all of us. You see that production is growing - even here we can say that we are not running out of anything. But the growth is slowing down. Copper production is not continuing the exponential growth it had been following in earlier times. What's happening? Let's give a look to the price trends.

As you see, copper prices have been following the same pattern we saw for crude oil. And that's not surprising: in order to extract copper, you need oil. It is a general rule that in order to extract anything - even oil - you need energy in one form or another. It is known that the extractive industry is a voracious consumer of energy. The quantitative estimates are variable, but we can say that perhaps about 10% of the total primary energy produced in the world is used for the extraction of minerals. Of this energy, a large fraction, (about 35% according to some estimates) is in the form of diesel fuel for mining machines; for bulldozers and the like. So, no wonder that a rise in oil prices has caused a rise in the price of most minerals.

There is also another problem and it is that not only the energy needed to extract copper is more expensive. It is also that it is becoming gradually more expensive to extract copper because the energy needed is increasing. It is a general problem: for any mineral, the high grade ores are the first to be extracted. But, as you run out of high grade ores, you must move to lower grade ores and processing lower grade ores is more expensive. That's the main effect of depletion. As I said, we are not running out of minerals; but we can say that we are running out of cheap minerals.

Now, I could tell you a lot more, but let me say that there are still some minerals that show a healthy growing trend, one is aluminum, for instance. That's due to the fact that high grade aluminum ores are still abundant and also that aluminum extraction requires a lot of electric energy and that energy is often generated by renewables, hydropower, for instance. So, aluminum is not subjected to the same problem of copper and other metals.

So, the production of some commodities is still increasing; what we can say in terms of a general rule is that we have a general problem of rising prices. Evidently, extraction costs are increasing everywhere and for all mineral commodities. Here are some data for an average of a few of them (incidentally, showing to you the difference that inflation makes; it is there, but it doesn't change the fact that there has been a huge increase in prices, recently):

Average price index for aluminum, copper, gold, iron ore, lead, nickel, silver, tin and zinc (adapted from a graphic reported by Bertram et al., Resource Policy, 36(2011)315)

Let me show you just a final example. The situation seems to be especially difficult for rare and expensive commodities and you surely have heard of the problem of rare earths; important minerals for applications in electronics. Here are the productive trends.

Production has not been increasing for at least five years and it is clear that there is a problem, here, even though the trends are not so clear as in other cases. About price trends, rare earths are a relatively small market and so what has been happening is a huge speculation phenomenon that caused prices to skyrocket. But, then, the bubble burst up and prices came down again in recent years. But not to the initial values, before speculation. Rare earth prices remain today about a factor 5 higher than they were 5-10 years ago.

We know is that the main producer of rare earths in the world is China and during the past few years China's production has been going down. Some people have said that China wants to use rare earths as a commercial weapon, but I think that is not the case. The fact is that mining rare earths is expensive and polluting and the Chinese government has been trying to clean up the operation. And that is expensive. As I said earlier on, pollution costs are an integral part of the cost of mining, even though that is not usually taken into account.

So, let me summarize the situation in just a few lines:

1. Overall mineral production still on the increase

2. Per capita production static or decreasing

3. Costs of production everywhere increasing

4. Pollution damage also increasing

All that is not surprising, actually it was expected. I said that "The Plundered Planet", is a report to the Club of Rome and you probably know the Club in reason of their first report, the one that was published in 1972 under the title "The Limits to Growth". It was a set of scenarios for the future that took into account mineral scarcity as one of the main parameters. The calculations have been redone and updated; here is the latest version of the main results, from the 2004 version

From "The Limits to Growth, the 30-year update" by D. Meadows et al.

Without going into the details of how the trajectory of the world's economy is modeled in this study, let me just say that it is based on physical factors - the main one being the increasing cost of extraction of mineral resources. This increasing costs was supposed to grow proportionally to the amount extracted. And you see, in the figure, how the curve for "resources" goes down with time, but also that troubles start much before running out of anything. It is because the high costs of extraction (and also the cost of pollution) are weighing down the economy, so much that it becomes impossible to keep industrial and agricultural production growing.

Now, the above shouldn't be taken as a prophecy; not at all. It was just one of the many possible trajectories that the world's economy could have taken. But, unfortunately, it looks like we have been following a trajectory close to this model. For instance, it seems clear that, as we approach the peak of industrial production that the model predicts, we are having problems in maintaining the growth of industrial production as we would like it to do. Here are some data for the industrial production in Europe (sorry that this image has labels in Italian, but I think you can understand it anyway):

Here, you see that after the crisis of 2008 there has been a certain return in industrial production. Germany almost managed to go back to the pre-2008 levels, but most European countries couldn't do that. So, I think this image tells us that the 2008 crisis wasn't just a financial crisis. It was something deeper and more structural. We can't say for sure that it is the start of that general decline of the worldwide industrial production that the scenario I showed to you sees for some moment around 2020; but it could be.

In any case, we clearly have big problems related to the high prices of mineral commodities which ar deeply affecting the economies of the world. Let me show you some data for Italy and Germany

As you see, we are dealing with huge sums spent for importing mineral commodities- several tens of billions of Euros. About the data above, note that we have the data for the imports of fossil fuels only, but to that we should add the cost of importing all the other mineral commodity. For Italy, I can tell you that it almost doubles the total: in 2012 the net balance amounted to some 113 billion Euros that Italy spent and that represents about 7.5% of Italy's GDP. I think that you should consider a similar fraction for Germany. Huge sums, as I said.

Now, consider that all these commodities have shown an increase in price of a factor that goes in the range of 3 to 5. You see that in the past few years, the added burden on the economies of countries which import mineral commodities has amounted to at least a few points of their GDP. Now, this is a heavy burden: we are talking of something of the order of 70 billion euros extra to pay for Italy alone - that can't fail to have an effect. And, as you surely know, it wasn't a good effect. The Italian economy is in deep trouble and I think that these extra costs are a major factor in the problem.

Germany survived increasing commodity prices better than Italy because the burden is lower in relative terms. This is because Germany produces some of its energy from domestic sources: coal and nuclear (which Italy doesn't have) and has also done a remarkable effort in renewable energy; which is also a domestic source. The difference is clear: here are some data (source: World Bank, elaborated by Google):

You see the difference in the graph and, if you happen to live and work in Italy, you feel the difference yourself. Germany has more or less recovered from the 2008 crisis, Italy hasn't. And I think that Italy's near complete dependency on imported mineral commodities is the crucial factor that makes the difference.

So, it is time now to recap and to conclude: clearly we have a problem here; and it is a big problem. But not one that's impossible to solve if we recognize it before it is too late. The solution lies, mainly, in the concept of "circular economy" that we are examining in this congress. And we know what that means: recycling, reusing, and being more efficient. But let me tell you one thing that I learned living in Italy: in order move towards a circular economy, you need resources and energy. Recycling has an energy cost, reusing does too - because you have to re-design practically everything. And even being more efficient has a cost: I see that in my job, which involves helping companies to make better products. Right now, Italian companies can't afford being efficient. It looks like a contradiction in terms, but think about that: they are fighting for survival; how can they invest in higher efficiency if the rewards for this will come only years in the future?

In short, if we don't have energy we can't do anything. If we have energy, we can recycle, we can reuse, we can be efficient and we can keep mining the resources which are still there, while we gradually move towards a circular (or "closed") economy.

This is the fundamental point, but it also has to be said in the right way, because it can be misunderstood and has been misunderstood. We need energy, but of the right kind: non polluting and not subjected to depletion. It should be clear that fossil fuels are not a solution: they can't solve the depletion problem, they can only worsen it. The faster you extract them, the faster you run out of them. And I can't stress enough that the problem we face is not just depletion, it is pollution in terms of climate change. The climate problem may be much more difficult and intractable than depletion.

So, the right word about energy is "renewable". And we can use the German term "energiewende" to indicate the energy transition. In the figure below, I am reporting some words by the British economist William Stanley Jevons, slightly modified (he was talking about "coal" rather than about "energy"; but the sense is the same)

So, we know what we have to do. But are we doing it? I am afraid that we aren't, at least not fast enough worldwide. Let me show you some data:

You see that the investments for fossil fuels dwarf those for renewable energy. Think of how much money is spent just to maintain more or less constant the production of fuels! And if you look at more general sectors, investments in sustainability compared to investments for infrastructure related to fossil fuels, you'll see that the trend is the same. Much more is spent to maintain business as usual - a society based on fossil fuels - than it is spent to create the energiewende, the transition to a cleaner, healthier, and more equitable society.

Note also a worrisome trend: investments in renewable energy went down in 2012 in comparison to 2011. Unfortunately, that points at the fact that when there is competition for scarce resources, the strongest competitor wins. And the fossil fuel industry is gigantic; with revenues in the range of several trillions of dollars per year for oil and gas alone. If the economic crisis continues, it is possible that we'll see the support for renewables shrink, while we'll see even more frantic and desperate efforts to pour everything we have into the fossil fuel industry in order to squeeze the last drops of fossil fuels out of the ground.

Why are we doing this? Who has decided to invest these huge sums for perpetuating an activity that is doing us gigantic damage and that we'll have to abandon anyway in a not too remote future?

I think we can say that it is us; most of us, at least. It is because we have been seeking for short term profits in our investments and - if we remain within that paradigm - we'll keep digging fossil fuels until we destroy our civilization and wreck the whole ecosystem.

On the other hand, it is also true that paradigm shift do exist. If we look at the figure above, we can see things in a more optimistic way. Think of how fast renewable energy - and sustainability in general - has been growing. Today we manage to spend some 250 billion dollars per year on renewable energy alone. Twenty years ago, it was almost nothing in comparison. So, that has been a remarkable progress that can make us optimistic for the future.

In the end, the way we spend our remaining resources is our decision. A decision that we make as professionals, as political leaders, as citizens of Europe, as citizens of the world, as human beings. And it is not impossible to take wise decisions if we just move our horizon a little farther than that of immediate financial returns.

To conclude, I would like to thank the whole staff of the Club of Rome for having made this report possible.