Manphela Ramphele (*) and Sandrine Dixon-Decleve, the co-presidents of the Club of Rome, at the start of the meeting of the Club in Cape Town on 5 November 2019 (**). These are somewhat rambling and incomplete notes written immediately after the end of the meeting.

Africa? What is Africa, exactly? A continent? A nation? A world in itself? Surely, it is enormous, variegated and complex. Personally, I had never crossed the equator in my life but these few days in Cape Town were enough to give me a new perspective of the world. It started with a small epiphany received from a Kenyan lady at the meeting of the Club of Rome who told me, "things are happening here."

Indeed, things are happening in Africa. You can see it from the data and the statistics but, perhaps, it is more a sensation. It is like a humming, a buzz, the feeling that something gigantic is stirring down below in the bowels of the continent. Something is happening, here.

When you land in Cape Town, you are struck first by the landscape: enormous rocky mountains all over the horizon -- remnants of the immense geological forces that shaped this section of the continent. Then, you move along the townships of Khayelitsha ("new home"), a seemingly infinite expanse of wood and iron shacks. Think of a European Gipsy camp multiplied by a factor 1,000 or more: the contrast with the skyscrapers, downtown, couldn't be starker. Not as grandiose as the mountains, nevertheless these settlements give you a sensation of human resilience, of the willingness to endure and survive, no matter how hard the conditions are.

And then you start getting a feeling of the place. It takes some time but, eventually, the pieces of the puzzle start coming together. Well beyond the trinkets for tourists and the cheap folklore, there are such things as an African vision, an African way, an African logic, and a certain feeling of being African. Of course, Africa is not a nation and it may never be one. Besides, it is sharply separated in two parts by the Sahara desert. But there is a certain continuity, a certain degree of shared beliefs that pervades the continent.

For instance, an African participant to the meeting generated another small epiphany for me when he said, "when we Africans disagree, we don't vote like you Westerners do. We discuss until we find an agreement and then there are no more contrasts." My first reaction as a Westerner was that it would never work in the West, but maybe that's because we have never been educated to believe that it is always possible to find an agreement when we need one. Then, of course, it may not work so perfectly even in Africa but, at least, if you start with the idea that you should strive to reduce contrasts, at least you won't exacerbate them. On this point, I had another epiphany from the words of a Chinese member of the Club who, in debating with someone else, said, "I am against you, but only 90%. I am with you 10%, and that may change to 90% with you: it is the principle of the Yin and the Yang, things always change and then become the same again." Maybe the Chinese and the Africans have something in common, for sure there is some wisdom, here.

So, there is such a thing as "Africa" that goes beyond the name of a continental plate. And there are people who define themselves as "Africans," a term that goes beyond the fact that they live on a certain portion of the Earth's continental plates. For sure, both Africa and the Africans have been badly misunderstood. If you live in Europe, and in Italy in particular, you can't avoid noting that Africans are seen as somewhat less than human, bands of renegades who land on our shores to steal our jobs and rape our women, people who can't keep themselves from breeding like rabbits. I am shocked myself at what I just write, but if you live in Italy that's what many people seem to think. The outburst of racism, there, has been simply unbelievable, but we have to believe it because it has happened.

Africa and the Africans have been invaded, enslaved, insulted, exploited, exterminated, misunderstood, slighted, despised, and much more. And yet, they are here. Despite all the problems: crime, corruption, violence, poverty, inequality, and what you have, Africa is here and Africans have something to say to the rest of the world. Will they be able to do that?

The challenges for Africa are enormous although, perhaps, not harder than for the rest of the world. One of these challenges is that the economic powerhouse of the sub-Saharan region, South Africa, is an economy that was built on coal, just like the European economies. And as all economies built on fossil fuels, the problem is how to move away from the original source of power. Clearly, South Africa is in big trouble, here. Apart from the need for phasing out coal, it is also a problem of supply, as it seems clear from the production data which indicate a peak in 2014.

In addition, the South African coal-fired power plants are obsolete and need to be phased out within the next two decades. South Africa also has a modest nuclear power production, but it doesn't seem to have the resources to increase it -- perhaps not even to maintain it. Then, there would be good chances for increased production of renewable energy but it seems that the South-African government suffers from the same failure of imagination as most Western governments: they can't imagine that energy can be produced without burning something, so they aren't encouraging renewable energy as much as it would be possible and advisable. And that's especially bad because South Africa provides energy for several other African countries and it is probably the only country of the region having sufficient resources for an energy transition. A decline in the South African production would reverberate all over the Southern African region.

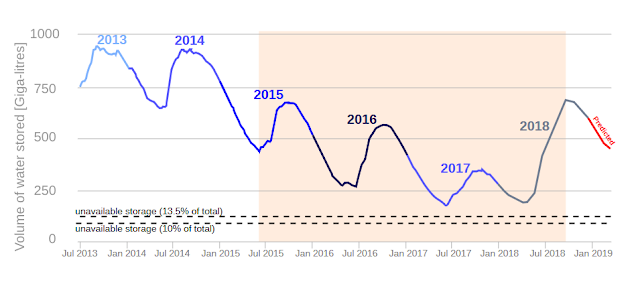

Then, there is the enormous question of climate change: what's going to happen to Africa as we climb the temperature ladder? We don't really know: some regions of the continent may become too hot for human habitation. The precipitation patterns might change: Cape Town had already a close call with a climate-related disaster with the drought that lasted until 2018.

Fortunately, the abundant rains of 2018 staved off the crisis, but Cape Town went close to be the first modern city in the world that could literally run out of water: it would have been the event known as "day zero," the day when nothing would come out of the taps anymore. Was it a problem related to climate change? And will the problem return in the future? We don't know and we can't know, but a future "water apocalypse" for Cape Town cannot be ruled out.

And finally, there is the question of population. In South Africa, the growth rate is slowing down, but the population curve shows no evidence of a flattening trend. At nearly 60 million people, today, it maintains a rate of increase of about 1.5% yearly. It is the inertia of a young population, compounded with legal and illegal immigration. And the economy is not expanding to match the trend: there are ominous signs not only of decline but of a much worse outcome that could include a social collapse undermining the reconciliation policies that had been successful in the 1990s.

Facing these enormous problems, it is no wonder that the Club of Rome has no miracle solution. Perhaps no solution whatsoever. Perhaps nobody in the world has solutions. What the Club could do was to state with the maximum possible force that we are in a climate emergency and that we need to go ahead with a climate emergency plan. Yet, at the meeting in Cape Town, some talks were so removed with the reality of the emergency situation to make one feel like screaming in rage. It takes time for some concepts to penetrate into people's consciousness. Climate change is such a gigantic thing that many people simply can't perceive it. It takes time. Likely, more time than we have.

One thing is clear, anyway, that whatever it is going to happen, we have no hope to do anything unless we do it together as that nebulous entity we call "humankind." We have created the problem, we are the only entity that (perhaps) can solve it. In this sense, the Cape Town meeting was in the best tradition of the Club of Rome as it was established by its founder, Aurelio Peccei. A truly international encounter of people who came from all over the world to bring their contribution and their ideas for the benefit of all humankind. Alone, the Club can't do that much but ideas can grow and spread and there is still hope. In this, Africans could give a major contribution.

So, where are we going? Onward, fellow humans!

(*) I am saddened to have to report that Manphela Raphele received the news of the death of a close family member just at the beginning of the meeting, so that she had to leave. Her presence was sorely missed and I can only offer my sincere condolences to her. Hopefully, she'll be soon active again with the many activities of the Club.

(**) Greta Thunberg has been able to popularize the concept that flying on a plane is inherently something evil. She is probably right and I have been thinking of that when I considered whether it was a good idea for me to fly to Cape Town. In the end, I decided to do that and I'll see to explain the reasons in a future post.