In this post, Pedro Prieto describes how South America, and in

particular Argentina, is affected by oil and gas depletion. A subject

almost never mentioned in the international press.

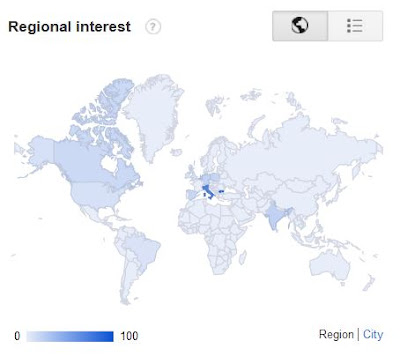

Also in this case, it is amazing to see the growing gap between

perception and reality: on the side of perception, wild enthusiasm and

reports about "the death of peak oil", on the side of reality, a

situation of shortages and difficulties, as Prieto describes to us in

detail for Argentina.

Guest post by Pedro Prieto

Argentina has been a gas exporter until 2007-2008 (Mainly

to Chile) and now is an importer (mainly from Bolivia and a

regasification plants in Bahía Blanca and recently in Escobar)

Source: Energy Export Data Browser

At the end of the 20th century, Argentina started exporting gas to Chile. Both Argentina and Chile believed that the supply was going to be increasing forever, but it was just a mirage.

I visited Chile invited by Compañía de Petróleos de Chile (COPEC) in 2011. I also had the opportunity to meet with top officials of the energy sector and academic experts in energy. They all believed that Argentinean supplies would last for decades. I could not understand why very professional people had such a belief, when data on reserves and possible flows of their neighbor country was probably available to them.

In fact, they embarked in an ambitious plan to develop pipelines across the Andes to supply Chile from the Argentinean network and ordered a number of gas fired power plants, trying to avoid or minimize, for instance, the heavy smog of Santiago, and for other economic reasons.

However, and without previous warning, Argentina reduced shipments to less than half. The obvious reason, as seen in the figures above, was the depletion pattern of the Argentinean gas and the need to prioritize their own domestic consumption.

This left overnight the Chileans with big, recently erected infrastructures idle and difficult problems to attend their growing internal energy demand, especially in electricity production for the extractive industries that they had expected to satisfy with the gas fired power plants.

They had to move fast to build a regasification plant in Quintero and later another in Mejillones. They did it in a record time, but certainly at a cost they had not imagined. This coincided with the sharp increase of fuel consumption that had started at the end of the past century. They needed to sign urgent contracts with LNG tankers and suppliers (i.e. Qatar), something that created for them what they called the perfect storm. Chile was in 2011 paying one of the most expensive electricity tariffs in the continent, partly due to this important bad planning.

Argentina started to import gas also at the end of last decade. Fortunately for them, they had pipeline connections from Bolivia, an important regional and neighboring gas exporter.

There were attempts from the Chilean side to get some Bolivian gas from the Argentinean network, but Bolivians were very clear in this respect: they have a long standing dispute on their outlet to the Pacific Ocean when coastal Bolivian territory was taken by Chileans in 1883 in the so called Pacific war, leaving Bolivia without access to the Pacific. So Bolivians are very sensitive in this respect; they still keep sueing Chile in International Courts and therefore told Argentineans that not a single m3 of Bolivian gas sent to them should end in Chile if they wanted to be supplied.

Argentina is producing today (2012) 102 Mm3/day and consumes 130 Mm3/day, importing 28 Mm3/day (1 Bcf/day). The imports will necessarily grow every year, as conventional gas is clearly in depletion; unless unconventional gas can replace the disappearing volumes of conventional.

Again, the costs of the infrastructure for such long distances, the purchasing power of the citizens and the volumes required will be a challenge. Gas prices in Argentina are heavily subsidized, but any attempt to put them at market levels could lead to internal revolts.

These big countries in Latin America have a problem to create infrastructures: although almost half of the Argentinean population is concentrated in Buenos Aires and its Province, many other cities are very distant from the capital city and from the gas deposits. Creating pipelines is very costly and not always (as we have seen before in the case of Chile) rewarding, unless there is a total security that the fuel is going to flow in volume and quality for much more time than that needed to amortize these costly infrastructures.

What is valid for natural gas is an anticipated warning of what will happen with the Argentinean oil. This year will probably see the end of the oil exports for Argentina. Then, the problems will multiply exponentially if no alternative resources are found (and fast).

Source: Energy Export Data Browser

The crisis we are now suffering in some developed countries in Southern Europe pales with respect to what these and many other countries have been suffering for decades.

Recently, the Argentinean government has banned wheat exports, to prioritize production for their own population and to avoid rising in the price of bread.

For a Spaniard, whose links with this Spanish speaking country are so close, this is something unbelievable. In the forties of last century, Argentina was one of the five most developed countries in the world and a net creditor country to the United States and United Kingdom (by the way, a debt that was never paid back by Great Britain or the USA). Argentina was considered for decades an important world breadbasket. It alleviated quite a lot of hunger, for instance, in Spain, after our Civil War, when in 1937 and 1988 shipped to our then blockaded country almost a million tons of grain to the then starving Spanish people.

The present situation in Argentina cannot be understood just in light of the artificially mounted financial debt or the internal corruption, but also from the interests of powers allied to internal corruption and promoting it to weaken this country and to spoil easier its vast natural and mineral resources, being the last one the fossil fuel ones. The problem comes together with intensive on extensive mechanized farming and cattle, which is heavily dependent of a permanent flow of fossil fuels. Cereal production (mainly wheat and corn) is being replaced by soya and other plants for biofuel production.

What follows is a recent article in an Argentinean newspaper on the situation in the country, that shows the close interrelation of energy supply stability and the functioning of many sectors of a modern society which depend on energy. An anticipated experience on how fast things will degrade, where priorities will have to be allocated, if rationing or restrictions are imposed, how unexpected feedbacks may distort productions, etc., when countries won’t be able to satisfy some energy supply minimums.

This, for the time being, appears to be temporarily, but there are growing signs that could expand and become permanent.

The cold wave has prompted an almost complete gas shortage in the biggest industries

The factories were forced by the Government to slow down their production to secure the supply to the residential sector.

Problems with the Compressed Natural Gas Plants

(GNC in Spanish)

23.07.2013 | 07:18 hs. · Source: La Nación

With the low temperatures a classic situation returned in the Argentinean winter: As the heat stoves increased their consumption, the main factories were forced to reduce the consumption to avoid problems in homes.

The residential demand ramped up to about 95 Million cubic meters (3,354 Mcf) yesterday, a historical record figure as per the experts. The government ordered to reduce the gas supply to a minimum in the manufacturing sector; in some cases, it was a complete stop. This situation will last at least until tomorrow.

The gas restrictions to industries affected all types of companies: iron, steel and aluminum (Siderar, Siderca, Aluar and Acindar), petrochemical (Profertil, Dow and Mega), automotive (Ford, Volkswagen and General Motors), food, cement and mining companies among others

At least 300 industries suffered important restrictions at national level.

The shortages did not only affect the factories. Metrogas reported by mail early in the morning to the responsible of the commercial center of Village Caballito, whose contract establishes interruptibility measures, to restrict the consumption to attend the higher domestic demand.

In Bariloche, low pressure affected the GNC service. Fernando Sammarco, responsible of the largest gas station in the city, in Beschtedt y Brown, said that he was warned one month ago from the Camuzzi center on the “possibility to have supply problems in winter”.

Yesterday, at 12.30, when the wind chill factor created a temperature of at -14.4ºC (6.8ºF), a company representative went to the three GNC stations in the city with a notification to close down the stations for an “indeterminate period.”

There were also cuts in La Pampa due to the cold wave.

The Industrial Union of Cordoba (UIC) was quoted as saying that in Cordoba there were restrictions to more than 20 companies

The economic impact of the gas shortages is difficult to assess, but it may range in millions of dollars, according to sector experts. As an example of the shortages, there was the stop of the petrochemical complex of Bahia Blanca, one of the main factory areas of the country. Dow, the polyethylene industry, stop operating. Not only gas was lacking, but also ethylene, a byproduct served by Mega, that also suffered a compete shortage.

Other raw material manufacturers, such as Cerri (TGS) and Refinor were also forced to stop consuming.

Enargas (the regulatory body in the gas sector) instructed transporters to prioritize the supply to the priority demand. Natural gas consumption authorized for the referenced day was 0 (zero) m3, “due to the (lack of) gas natural injection available and climatic harshness.

The email received by an industry from the Camuzzi distributor, attending the Central and Southern part of the country indicated “9,300 kcal”

Similar messages were sent by Gas Natural Fenosa and Metrogas to their industrial customers. At least half of “firm customers” (paying more for the supply to avoid shortages) suffered supply shortages.

Gasnor, a distributor, ordered a strong consumption reduction, which prompted anger of the sugar processing mills in Tucuman and Jujuy. The shortages ranged from companies suffering total cuts to others that could maintain only the “technical minimum.”

The natural gas sector has not been publishing daily statistics for several years. According to some sources from the sector, knowing the system daily operation, the average shortage to the industry was 50 percent. “The factories use to demand 40 million m3 and yesterday they received about 20 million m3”, said an executive, on the condition of anonymity.

The government also paid part of the energy costs. At 17.00 hours, the consumption reached a 19,998 MW peak a huge figure. The generating companies, which are covering the demand, had to replace gas they use and prefer to produce electricity by liquid fuels. The reason is that only 18 million m3 of gas were available, only 60% percent of the volume they use to produce electricity. The rest was covered with the more expensive liquid fuels, paid by the State.

Now we can understand how desperation can make virtue out of necessity and the interest to develop any unconventional possibility.

The Vaca Muerta shale deposit in the Neuquen Basin in Patagonia, some 1,200 km from Buenos Aires and about 500 km. from the nearest port in the Atlantic, is the last hope. Repsol-YPF started exploring this area in 2010 and it had drilled and completed about 30 wells producing some 5,000 barrels/day. In may 2012 YPF was expropriated (nationalized) again by the Argentinean government.

It is not clear if the official announcement of the discovery made by Repsol, of this huge deposits (November 2011) shortly before the expropriation/nationalization of YPF, was an aseptic notification of a reservoir or if it was more due to the need to raise their then decayed stocks. These days, the hype of the shale gas and oil in the United States had a growing number of believers and potential investors. The values for the reserves in these deposits declared by Repsol/YPF and then by the media vary in a wide range. It is probably due to the big and frequently interested confusion between reserves and resources and also to the declared types of shale (or marl), the depths and the carbon content. The “technically recoverable” gas and oil is another name of the game. They are being hyped as the third largest deposits of shale oil in the world.

Originally evaluated as close to 1 billion barrels of proven reserves, have been since then increased to 12 Bb in prospective oil resources and 21 Bboe of gas.

In any case, on the first press releases of Repsol-YPF on the big potential of Vaca Muerta, the Argentinean government “bought” the argument of gigantic reserves and proceeded to the expropriation/renationalization of YPF, more likely also for political or financial reasons and trying to gain popularity, than for a reasonable replacement plant in time of their dwindling conventional reserves.

More than one year after the expropriation/renationalization, the Argentinean government is still struggling with the claims of Repsol in the national and international courts and also for lack of adequate financing. It may appear that one year is nothing (in fact it isn’t!) for developing oil or gas fields, but for Argentina it may represent the year in which the changed from exporting to importing oil, which may bring political, economic and social upheavals as it is happening right now in Egypt.

Another problem for shale deposits is that the demand for financing grows at a much higher pace than the oil or gas flow from shales. Repsol-YPF did the announcement and, immediately afterward, they evaluated their investment needs to develop Vaca Muerta in about 25 Billion dollars per year in the first 10 years.

Negotiations were held with Chinese investors, but apparently without results. It may have happened that Chinese did not buy the miracle of shales and perhaps their required collaterals were more in line with the need to secure huge productions of soya in huge single crop farming in the fertile lands they are lacking in China, than to accept being paid back with a portion of the oil and gas extracted.

Today, the development of Vaca Muerta is still stagnant. Many big energy corporations appear and disappear to negotiate with YPF and the desperate Argentinean government behind it. It is easy to sense that many will be offering sophisticated horizontal drilling equipment, sophisticated compressors and pumping systems, autonomous generator equipment, consulting services, know-how or sophisticated (and poisonous) chemical cocktails under copyright. Of course, like in most of the shale businesses these actors do not wait for oil and gas to exctracted and sold to have their money back.

Repsol is still looking to defend its expropriated interests there and threatens not only the Argentinean government, but also to any other corporation daring to enter in business with its expropriated, now national company YPF. Of course, the size and lobbying capacity of Repsol in front of international courts or instances (i.e. IMF), is of no big concern for much bigger energy corporations.

Additionally, Vaca Muerta has no infrastructure whatsoever. Pipes for water, pipes for gas and oil will have to be built from scratch and cover long distances in many cases and have pump stations in the way. Refineries and processing units will be needed. Even the roads in the area, if existing (very, very few) are made of “ripio” (compressed gravel) and will be destroyed quickly by the huge amounts of heavy trucks following the mobile circus that the exploitation of shale plays represents, moving ahead, well after well each few months.

In May 2013, YPF and Chevron announced an agreement to start exploiting Vaca Muerta. The latter has been sued in Washington by Repsol. In any case, we are already in 2013, the key year for Argentina to change from exporter to importer of oil and what they have signed is to invest 1.2 billion dollars that could eventually increase to 12 billion $ by 2015. Other licenses are given in the area to companies like Pluspetrol, PAE, Exxon, Apache and Shell, but the total rig count in the area is of only a few tens. The oil production in the region, three years after having started exploitation is of few thousand barrels a day.

For a country that consumed 612 kb/d and produced 664 kb/d in 2012, but that was producing 900 kb/d of basically conventional oil in 2003 (thus decaying at a 3%/year), they desperately need a miracle. The foreign investors, if any, will first look how to recover their investment and then they may attend the internal demand of oil and gas. Given the financial structure of the main investors in the “successful” shale plays in the very developed US, it may take many, many years to see the second covered. It must be very interesting to analyze the fine print of the contracts for the collaterals demanded to Argentina by the foreign investor. Probably nothing new: more debt against not only future oil and gas, but also other valuable natural assets, like agriculture, minerals or fisheries. Business as usual.