Monument building cycle of the Mayan civilization. From "Sylvanus G. Morley and George W. Brainerd, The Ancient Maya, Third

Edition (Stanford University Press, 1956), page 66.". Courtesy of Diego Mantilla.

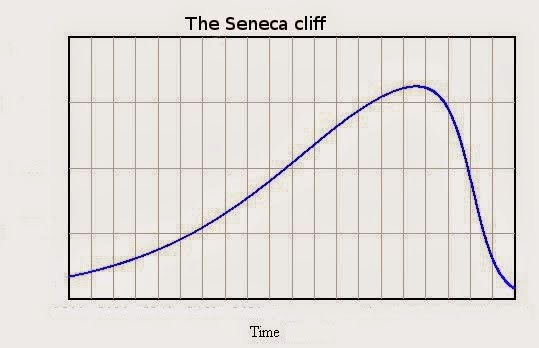

Once you give a name to a phenomenon, you can focus your attention on it and learn more and more about it. So, the "Seneca Cliff" idea turns out to be a fruitful one. It tells us that, in several cases, the cycle of exploitation of a natural resource follows a forward skewed curve, where decline is much faster than growth. This is consistent with what the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote: "increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid." With some mathematical tricks, the result is the following curve:

This curve describes the behavior of several complex systems, including entire civilizations which experienced an abrupt collapse after a long period of relatively slow growth. In my first post on the seneca cliff, I already discussed the collapse of the Mayan Civilization (*)

Here, you can see the the Seneca behavior, although the data for the Maya population density seem to be rather qualitative and uncertain. However, the data that I received recently from Diego Mantilla (see at the beginning of this post) are clear: if you take monument building as a proxy for the wealth of the Mayan civilization, then the collapse was abrupt, surely faster than growth.

Something similar can be said for the ancient Egyptians, although the data for pyramid building are more sparse and uncertain than those for the Maya. Finally, also the Roman civilization appears to have collapsed faster than it grew.

So, the Mayans didn't do better than other civilizations in human history. As other civilizations did, they moved toward their demise by dragging their feet, trying to avoid the unavoidable. They didn't succeed and they didn't realize that opposing the collapse in this way is a classic example of "pushing the levers in the wrong direction". It can only postpone collapse, but in the end makes it more rapid.

Will we do any better than the Mayans? One would hope so, but........

(*) Dunning, N., D. Rue, T. Beach, A. Covich, A. Traverse, 1998, "Human - Environment Interactions in a Tropical Watershed: the Paleoecology of Laguna Tamarindito, Guatemala," Journal of Field Archaeology 25 (1998):139-151.