The idea of the "Yellow Peril" about China was once a common way of thinking. Here I am illustrating how bad could that be from a short story by Jack London. Given the current situation, I wouldn't bet that this kind of attitude couldn't return, together with proposals for wiping out the Chinese population by means of biological warfare. Image source

As I was surfing the Web looking for data about how the Chinese government managed the COVID epidemic, I found this short story written by Jack London about a future where China grows so much that the Western Powers band together to exterminate the Chinese. They do so by means of a campaign of biological warfare that kills most of the Chinese population. Then, the survivors are killed by conventional weapons by the Western armies that invade China. Finally, Westerners sanitize and colonize the empty Chinese territory, resulting in an era of "splendid output."

I have to say that I was a little shocked: I knew Jack London for his "The Call of the Wild" and "White Fang," both could be seen as enlightened stories about the power of nature and the value of animal life. That London, who could so well understand the mind of a wolf, would so badly misunderstand the Oriental mind was a little unsettling, to say the least. On this, I later found that several critical essays on this story maintain that it was to be understood as ironic. Maybe, but I am sure many people who read the story took it at face value.

So, we have here a description of a racially driven extermination of an entire population, done using biological weapons, the whole is said in glowing terms and apparently completely approved by the author. Hard to think of something more evil than this. Remarkable how this story could be published without anyone, apparently, complaining.

But the curious thing about this story is that, although the story of the "Yellow Peril" seems to have gone out of fashion (fortunately), people in the West still badly misunderstand China. For instance, recently it has become fashionable to accuse China to have waged, or attempted to wage, a biological war against the West using the COVID-19 as a weapon (unlikely, to say the least!). Also, the fact that China managed to contain the epidemic much better than Western countries didn't generate a friendly attitude.

The Western propaganda machine has been set in motion in this issue and the result is a wave of anti-Chinese feelings. I have seen many comments in the social media of people who seem to see the Chinese in the same way as they are described in London's story: a nation of incomprehensible and brutish individuals who eat bats and dogs and cultivate other disgusting habits. We haven't arrived yet to the proposal of exterminating the Chinese using biological weapons, but, who knows? The future always surprises you and the idea of "ethnic bioweapons" is circulating and probably being studied in the world's bioweapon labs. On this, London could have been prophetic, unfortunately.

Anyway, if you have 5 minutes, you can use them to take a look at this horrible thing that I still hope was to be understood as irony.

"The Unparalleled Invasion," by Jack London, 1910.

Some excerpts (you can find the whole text here)

What they had failed to take into account was this: THAT BETWEEN THEM AND CHINA WAS NO COMMON PSYCHOLOGICAL SPEECH. Their thought- processes were radically dissimilar. There was no intimate vocabulary. The Western mind penetrated the Chinese mind but a short distance when it found itself in a fathomless maze. The Chinese mind penetrated the Western mind an equally short distance when it fetched up against a blank, incomprehensible wall. It was all a matter of language. There was no way to communicate Western ideas to the Chinese mind. China remained asleep. The material achievement and progress of the West was a closed book to her; nor could the West open the book. Back and deep down on the tie-ribs of consciousness, in the mind, say, of the English-speaking race, was a capacity to thrill to short, Saxon words; back and deep down on the tie-ribs of consciousness of the Chinese mind was a capacity to thrill to its own hieroglyphics; but the Chinese mind could not thrill to short, Saxon words; nor could the English-speaking mind thrill to hieroglyphics. The fabrics of their minds were woven from totally different stuffs. They were mental aliens. And so it was that Western material achievement and progress made no dent on the rounded sleep of China.

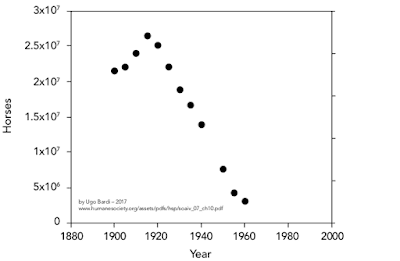

For many centuries China's population had been constant. Her territory had been saturated with population; that is to say, her territory, with the primitive method of production, had supported the maximum limit of population. But when she awoke and inaugurated the machine-civilization, her productive power had been enormously increased. Thus, on the same territory, she was able to support a far larger population. At once the birth rate began to rise and the death rate to fall. Before, when population pressed against the means of subsistence, the excess population had been swept away by famine. But now, thanks to the machine-civilization, China's means of subsistence had been enormously extended, and there were no famines; her population followed on the heels of the increase in the means of subsistence.

There was no combating China's amazing birth rate. If her population was a billion, and was increasing twenty millions a year, in twenty-five years it would be a billion and a half - equal to the total population of the world in 1904. And nothing could be done. There was no way to dam up the over-spilling monstrous flood of life. War was futile. China laughed at a blockade of her coasts. She welcomed invasion. In her capacious maw was room for all the hosts of earth that could be hurled at her. And in the meantime her flood of yellow life poured out and on over Asia. China laughed and read in their magazines the learned lucubrations of the distracted Western scholars.

But on May 1, 1976, had the reader been in the imperial city of Peking, with its then population of eleven millions, he would have witnessed a curious sight. He would have seen the streets filled with the chattering yellow populace, every queued head tilted back, every slant eye turned skyward. And high up in the blue he would have beheld a tiny dot of black, which, because of its orderly evolutions, he would have identified as an airship. From this airship, as it curved its flight back and forth over the city, fell missiles - strange, harmless missiles, tubes of fragile glass that shattered into thousands of fragments on the streets and house- tops. But there was nothing deadly about these tubes of glass. Nothing happened. There were no explosions. It is true, three Chinese were killed by the tubes dropping on their heads from so enormous a height; but what were three Chinese against an excess birth rate of twenty millions? One tube struck perpendicularly in a fish-pond in a garden and was not broken. It was dragged ashore by the master of the house. He did not dare to open it, but, accompanied by his friends, and surrounded by an ever-increasing crowd, he carried the mysterious tube to the magistrate of the district. The latter was a brave man. With all eyes upon him, he shattered the tube with a blow from his brass-bowled pipe. Nothing happened. Of those who were very near, one or two thought they saw some mosquitoes fly out. That was all. The crowd set up a great laugh and dispersed.

The wretched creatures stormed across the Empire in many-millioned flight. The vast armies China had collected on her frontiers melted away. The farms were ravaged for food, and no more crops were planted, while the crops already in were left unattended and never came to harvest. The most remarkable thing, perhaps, was the flights. Many millions engaged in them, charging to the bounds of the Empire to be met and turned back by the gigantic armies of the West. The slaughter of the mad hosts on the boundaries was stupendous. Time and again the guarding line was drawn back twenty or thirty miles to escape the contagion of the multitudinous dead.

During all the summer and fall of 1976 China was an inferno. There was no eluding the microscopic projectiles that sought out the remotest hiding-places. The hundreds of millions of dead remained unburied and the germs multiplied themselves, and, toward the last, millions died daily of starvation. Besides, starvation weakened the victims and destroyed their natural defences against the plagues. Cannibalism, murder, and madness reigned. And so perished China.

They found China devastated, a howling wilderness through which wandered bands of wild dogs and desperate bandits who had survived. All survivors were put to death wherever found. And then began the great task, the sanitation of China. Five years and hundreds of millions of treasure were consumed, and then the world moved in - not in zones, as was the idea of Baron Albrecht, but heterogeneously, according to the democratic American programme. It was a vast and happy intermingling of nationalities that settled down in China in 1982 and the years that followed - a tremendous and successful experiment in cross-fertilization. We know to-day the splendid mechanical, intellectual, and art output that followed.