|

| Solar plant near Rüdersdorf, Germany 2014, © Molgreen, CC BY-SA 4.0 |

(Reblogged from blog.wozukunft.de)

Guest post by Gregor Hagedorn

Many people, including myself, fear that the great acceleration (

1,

2) of our consumption and destruction of resources such as land, biodiversity, soil, minerals, and fossil energy sources, could lead us into a catastrophe. Other people point out the positive side of near-exponential growth in various fields: renewable energy production, "biotechnology and bioinformatics; computational systems; networks and sensors; artificial intelligence; robotics; digital manufacturing; medicine; and nanomaterials and nanotechnology"

(Peter H. Diamandis & Steven Kotler 2012. Abundance: The Future Is Better Than You Think). Others propose that the roadmap to prevent the climate catastrophe should follow an exponential "carbon law", modeled on Moore's law for the semiconductor industry (

Rockström et al 2017).

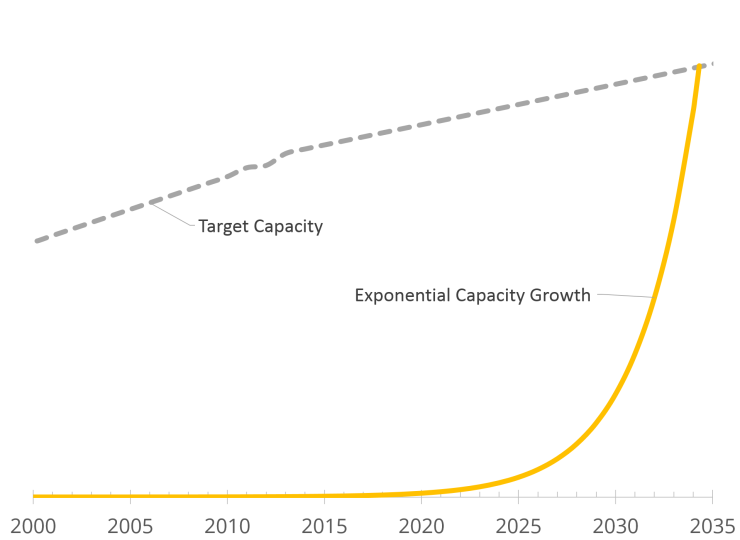

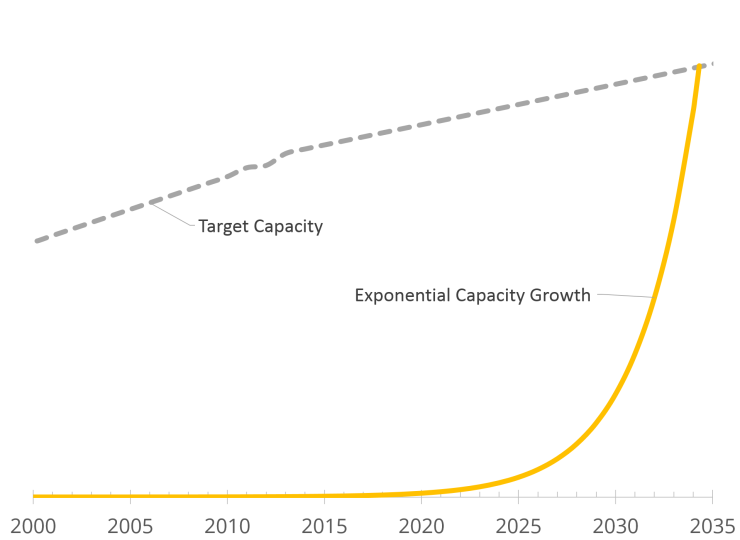

Exponential growth models leading towards sustainability certainly offer hope. An example might be the renewable energy transition: the growth of

cumulative solar energy capacity is indeed almost exponential.

|

| Exponential Growth in Renewable Energy Production Capacity. The gray target final energy capacity is assumed to be slowly increasing as a result of a combination of energy savings in rich countries and equitable growth in poor countries. (© Gregor Hagedorn, CC BY-SA 4.0) |

However, looking at the graph, it is clear that the assumption of unchecked exponential growth makes no sense. An extrapolation of the historical annual growth rate (39.14%) means that the final doubling of capacity occurs in the last 25.2 months. Huge productions facilities would have to be built for the necessary solar panel and wind turbines – to be used only for a very short time.

Most scientist and economists are aware of this, but I have experienced many lay people and politicians taking “exponential problem solving” at face value – which may be a problem.

Renewable energy capacity growth as an example

What would a more realistic model be? As a biologist, I am acquainted with logistic growth models limited by a capacity factor such as the available food or land. But organisms will reproduce until the capacity is exhausted, often going into overshoot followed by a period of population collapse (die-off). Humans have foresight (at least sometimes). And investors usually calculate the profitability of investments.

Bardi & Sgouridis 2017 evaluate the effect of time of return on energy investment of renewable energy production installations (e.g. photovoltaic installations, wind parks). In my understanding, this is relevant but different from the effect of the economic return on investment on the factories producing the solar panels, wind turbines, etc. What effect does a minimum life-span of these factories have on the energy transition? As I could not find a publication (please comment, if you know one!), I decided to investigate this.

As I could not find a publication (please comment, if you know one!), I decided to investigate it myself. I will focus on a single of these transformation dynamics, the economics of investing. This is not meant to be a comprehensive model, encompassing the complexities of the real world and aimed at making actual predictions. I think of it more as a thought experiment to estimate the difference between exponential growth and a reasonable return-on-investment on production facilities under otherwise ideal growth conditions. Basically, I assume that any new factory should be running, with reinvestments and upgrades, for 30 years. The following indented text documents the assumptions behind the model (skip ahead, if you like).

1. To simplify, I use the capacity growth value for solar photovoltaic panels (0.105 GW 1992 to 405 GW projection 2017, = 39.14% annual or 2.78% monthly growth) as representative for the entire renewable energy mix needed in the future (the combined growth rate of wind turbines, concentrated solar, geothermal, etc. would lead to a more complex and more realistic picture).

3. After 2014, consumption is extrapolated using assumptions about energy savings and equitable growth needed for poorer countries. I assume that the combination of energy savings and additional energy needed for equitable growth for a good life on 9-12 billion humans will be doubling global final energy consumption between 2014 and 2100 to about 220 PWh/year. The slope of this increase is significantly smaller than the past increase, but the sudden transition into linear growth is a strong simplification. The end result roughly matches the common assumption of a demand of 2kW average equivalent power/person in 2100 (see., e.g.,

Bardi & Sgouridis 2017); 12 billion people * 2 kW = 24 TW average = ca. 210 PWh/year.

4. Global final renewable energy

capacity is calculated by assuming we need 8 × average output as peak output; compensating for within-day volatility, seasonal volatility requiring long-term storage, average capacity factor (cloudy/non-windy days), regional volatility (if Portugal and Germany are to supply each other to reduce volatility, they both need large excess capacity). This is a wild guess. The

capacity factor for

solar in Germany is around 10%, wind between 20 and 50%, but we talk global here and I have not good data for a global average. Please help if you can provide better global, cross-technology estimates for the relation between peak capacity and annual final renewable energy consumption!

5. The model assumes that factories producing solar panels, concentrated solar plants, wind turbines, etc., require a production time of 30 years for an economic return on investment.

6. During this time, re-investments occur making production cheaper or increasing the production capacity (higher wind turbine/solar panel output, or more efficient technologies, generating more power per item). Since both solar panels and wind turbines are relatively mature technologies, I assume an increase in capacity for a given factory of 30% over the 30-year lifetime (modeled as 1.32% per year in the first 20 years, with no further investments and gains in the final years). Again, this is a wild guess; better estimates are most welcome. (Different assumption for improvement rates change the outcome only marginally since it is mostly equivalent to the addition of small factories with a shorter lifespan, decreasing the average lifespan of a factory per production capacity.)

7. The model includes a replacement rate for older renewable energy installations. The aging-related yearly capacity loss of various renewable energy solutions (e.g. 0.5-1% in solar panels) is ignored here, considering the assumptions for overcapacity above. For solar the panel warranty is usually 20-25 years, but usability may be much longer. I assume 20% replacement for yearly cohorts after each of 20, 25, 30, 40, and 50 years (i.e. max lifespan 50 years). The 20-year category includes replacements for storm damages, etc.

8. After 2051, the production time of some factories is extended for a number of years, to reduce the ensuing production fluctuations. Again: The real world is much more complex. Investment into production plants depends on many economic factors: workers, capital, interest rates, location and regional planning, regulatory conditions, supply chains for raw material and preprocessed parts, etc. And, again, this is no prediction model, but a mind-sized analysis of one factor!

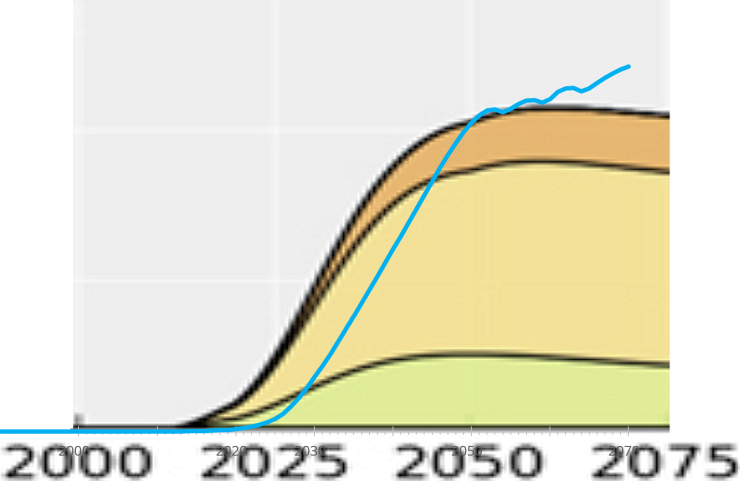

The resulting graph looks like:

|

| Factory-depreciation-limited (blue) versus exponential growth (yellow) in renewable energy production (© Gregor Hagedorn, CC BY-SA 4.0) |

What did I learn?

"Exponential growth" only matters in the beginning. The vast majority of capacity increase happens between 2027 and 2051 in a near-linear fashion. Under the parameters chosen, only 7.8% of the capacity is produced under the exponential growth model. Clearly, this result depends on the growth rate and the expected lifespan of production facilities for solar panels, concentrated solar power, wind turbines, etc. The result will be similar whenever the factory lifespan is similar to the time it takes to reach the capacity growth target.

Some additional, minor observations (skip ahead, if you like):

1. Whereas under a fully exponential calculation the energy production capacity for 100% Renewable Energy is reached 2034, it takes until 2051 in the present calculation. (Note that this may still allow reaching the Paris climate goals; but also note that the calculation does not deal with issues like volatility, storage, transport, stranded assets, etc.).

2. With regard to new production capacity (factories) in the present calculation: 2027 is "peak acceleration", followed by five years in which production capacity continues to increase, but with less new capacity each year. And that is it. Under the (arbitrary!) assumption that you need at least 30 years return on investment into a new plant, it would be uneconomical to build additional production facilities between 2033 and 2051. From 20151 on, replacement of older factories and increasing demand for solar panel and wind turbine replacement creates a new market for the establishment of new production facilities.

3. Between 2051 and 2100, a period of alternating over- and underproduction occurs in the present calculation, which uses global yearly factory cohorts and an inflexible re-investment / capacity upgrade scheme. In reality, many individual factories would have different lifetimes, be upgraded at different times, and some factories might make losses and be closed prematurely. All of this would enable the markets to track demand more flexible. Still, being able to track a market which transitions from a strong growth market to a weak growth market which then transitions into an increasingly strong replacement market will be a challenge. Some Lotka–Volterra-like oscillations are in fact not uncommon in markets, see, e.g., the DRAM production in the semiconductor industry.

4. The production capacity for solar panels, wind turbines, etc. in 2017 is about 114 GWpeak/year (please comment if you think this number is incorrect!). Under my assumptions (and in order to achieve the target capacity by 2051), production capacity must very quickly rise to about 5700 GWpeak/year in 2032. It then grows slowly, through productivity increases in existing factories to a peak of 6643 GWpeak/year in 2047. The exact values and years depend on many assumptions in this calculation and are likely to be only very rough estimates. However, the estimates show that building sufficient production capacity for the energy transition is a huge challenge – and a huge market opportunity.

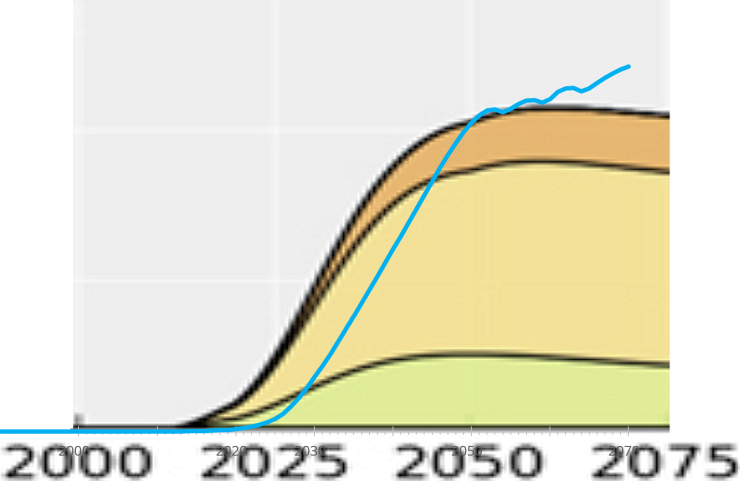

5. Comparing the results with the return-on-energy models from

Sgouridis et al. 2016 (see the crude graph below): a) total peak capacity in 2075 is about 100 TWpeak, less than then 165 TWpeak in our calculation; b) total capacity is falling after 2050 in Sgouridis et al. 2016; c) the main growth occurs about 8 years earlier; d) the transition towards capacity is smoother, i.e. in the last 8 years capacity is added slower than in my (purely factory-output-optimized) model.

|

| Comparison of model with result of Sgouridis et al. 2016 (© Gregor Hagedorn, CC BY-SA 4.0) |

General Conclusions

The idea that a future acceleration of technological progress at an exponential rate will solve many problems has several proponents, the best known of which are perhaps Diamandis & Kotler. Their 2012 book has been widely reviewed and criticized. Patrick Tucker (2012,

An Awesome Adventure to the Future) applauds them for encouraging the view that problems can be solved. But as Dale Carrico (2012,

Schlock and Awesome; Or, The Futurists Are Worse Than You Think) points out, uncritical wishful thinking without regard to problems and limitations is

"escapism from the real present, what it offers as solutions are nothing but distractions from problems". Gregor Macdonald (2012.

'Cornucopians in Space' Deliver a Dangerously Misguided Message – Optimism has its dangers) notes that Diamandis "is an adherent to the notion that exponential growth in technology will eventually reach a crescendo, thus offering humankind super-solutions at a kind of hyperspeed rate of change." But while technological progress is helpful and welcome, "the magnitude of the world’s present challenges cannot wait for the array of potential solutions that

may start to work". He warns that "celebrating the success of solutions before they have actually arrived – indeed, well before they have arrived, is no solution at all". Michael Marien (2012,

globalforesightsbooks Book of the Month) observes that the "techno-ecstatic focus of Singularity … serves to obscure the need for “soft” social technology that is of equal if not greater importance" and "questions are ignored about how the new abundance will be distributed in a world of massive and increasing inequality, where many governments are running huge deficits and hamstrung by ideological gridlock and obsolete ideas", conceding that "As inspirational futurism suggesting possibilities of a better world for all, there are certainly many good budding ideas here that may bloom."

Some of the general problems of belief in unchecked growth are very nicely exposed by Tom Murphy (2012,

Exponential Economist Meets Finite Physicist) - highly recommended!

One of my own conclusions is, that exponential decay, such as the aforementioned "carbon law", makes more sense than the growth case. Overall, however, the assumption that initial large reductions can be achieved with relatively low investment, followed by decreasing reductions at increasing cost is more plausible than the case of exponential growth. Again, this cannot be repeated forever, as cost becomes prohibitive, but this is not really necessary to achieve the goals intended by the "carbon law" proposal.

My own view is that it is good to point out signs of hope and progress (some of my favorites are, e.g.,

Hans, Ola & Anna Rosling - do read the new book 'Factfulness',

Max Roser and his co-workers, or

Dina D. Pomeranz). And we all hope that innovation can solve at least some of our problems.

However, most people already expect miracles from technology. While innovation may follow exponential growth for some time, this will in all likelihood always change to a different growth model over time

1. The calculations above are only an example.

Scientific limits of the earth system, economic limits (as in the example above), sociological and psychological limits of humans and their societies, as well as the potential for exponential technological growth, need to be viewed together. Ignoring parts of the system will not lead to a solution.

But worse: I see the perceived need for and the creed in endless future technological innovation as a distraction. As misleading. as prolonging our current phase of procrastination and not solving the many problems we can already solve right now.

It is not true that we are currently desperately trying to survive and have no other option than to send our own children into a slavery of food, energy and resource scarcity. It is not true that our only chance is to hope for yet non-existent technologies.

The truth is: We have the technologies, we can solve the energy (see, e.g.,

Bardi & Sgouridis 2017), food, biodiversity, transportation, equity, etc. problems.

But we are not using the solutions at the necessary scale. We are procrastinating and seeking excuses: whether it is that the problem cannot be solved or that they will solve themselves thanks to a sudden explosion of exponentially growing innovation. We are celebrating ourselves in the media for deploying positive solutions at small scales. At the same time, we are directing the general economy through taxes, tariffs, and subsidies at many orders of magnitude into the opposite, destructive direction.

We are not building a house for our children,

we are burning it down. Our greed for money, for personal power and sex, for eating meat and other luxury foods, for playing with ivory tower problems has us care more about ourselves than about the future of our children.

Notes

1 I believe this even applies to the tech development under the scenario of technological singularity, wiping out humanity – but this is a different discussion...

References

Ugo Bardi & Sgouris Sgouridis 2017.

In Support of a Physics-Based Energy Transition Planning: Sowing Our Future Energy Needs. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, December 2017, 2:14,

doi:10.1007/s41247-017-0031-2

Rockström, Gaffney, Rogelj, Meinshausen, Nakicenovic, Schellnhuber 2017.

A roadmap for rapid decarbonization. Science 355: 1269-1271.

doi:10.1126/science.aah3443

Sgouris Sgouridis, Denes Csala & Ugo Bardi 2016.The sower's way: quantifying the narrowing net-energy pathways to a global energy transition. Environmental Research Letters, Volume 11, Number 9. http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/9/094009/meta