In the book "Hitler's Willing Executioners" (1996) Daniel Goldhagen argues that the Germans couldn't possibly have missed that their government was exterminating the Jews and other ethnical groups. But it is also possible that most Germans were misled by "deception by omission." If a subject is not mentioned in the media, just like the extermination of the Jews in Germany, it disappears from the collective consciousness. The same phenomenon may be at work with the Trump government in fields such as climate change. And it seems to be working.

This post was slightly updated in 2021

Imagine you are a German citizen living in the early 1940s. Would you know that the German Government was engaged in the extermination of millions of Jews and other ethnical groups? The question is controversial: one interpretation is that the Germans couldn't possibly be unaware of what was going on. But it is also true that the extermination was never mentioned in the German media. Ordinary Germans might have been aware that the Jews were being mistreated, but they had no way to know the extent of what was going on. In the cacophony of news about the ongoing war, the issue of the Jews didn't register as something really important. Something similar happened in Italy with the defeat of the Italian army in Russia in 1943. The disaster was never mentioned in the media, and it didn't play a role in the public perception of what was going on.

The propaganda techniques used in Germany and in Italy during WWII were still primitive, but they were effective in the field we call today "perception management." The technique of denying information is called "deception by omission." A good description is reported by Carlo Kopp.

A prerequisite for Deception by Omission is that the victim has poor a priori knowledge or no a priori knowledge or understanding of what the attacker is presenting to be a picture of reality. A misperception of reality favourable to the attacker can be implanted if the victim can be induced to form a picture of reality based only upon what the attacker presents. .. Deception by omission is a very popular technique in commercial product marketing and political marketing since it permits attacks without resorting to making provably untruthful statements. .. The deception by omission technique is often successful due to laziness or incompetence on the part of a victim population.Kopp also notes how Deception by Omission is often coupled with two other techniques known as "Deception by Saturation" (saturating the target with irrelevant information) and "Deception by Spin" (presenting correct information in ways that make it favorable to a specific interpretation).

Now let's see how the technique works in our times. Note that I am not saying that the US government controls the media in the same way as the Nazi government did during WWII. But the US government does control the source of the news. If the government doesn't provide news about something (or provides only scant news) then the journalists have little to show to the public. If the subject doesn't appear on the media, the public loses interest in it. And if the public loses interest in something, journalists are even less motivated to write about it. It is a feedback loop: we may reasonably suppose that it is what we are seeing in the case of the targeted killings program.

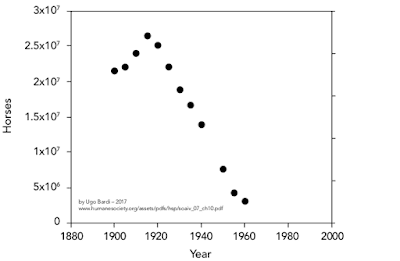

Let's see now how the same mechanism may be at work in the case of global warming and climate change. First of all, here are some results from Google Trends.

I think it is reasonable to say that there has been a detectable decline during the past year or so (note that the 2017 spike corresponds to Trump's announcement that the US would withdraw from the Paris Climate Treaty). This interpretation may be confirmed by the most recent Gallup poll. In March 2018, Americans were less convinced that climate change is a threat than they were in 2017.

Other data from the same poll indicate that the change is mainly caused by a decline in the number of "concerned" people, while the fraction of skeptics and lukewarmers remains approximately the same.

So, what's happening? The most likely explanation is that it is the result of deception by omission. There is no doubt that the US government is muzzling scientists and scientific agencies and Trump himself has been silent on climate change despite his many tweets. Nowhere the strategy of the administration is clearer than with the story of the "red team/blue team" debate on climate, proposed by the former EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt. The idea was soon nixed by the administration, correctly if seen in the framework of a deception by omission strategy. If there had been such a debate, no matter which side could have given the impression of being right, the public would have perceived climate change as an important issue.

Now, of course when discussing these matters one always risks to be branded as a conspiracy theorist and ignored. But we don't have to think that some people collected in a secret room to plan dark and dire things against us. It is just that ignoring climate change is in the best interest of several sectors of society. The current elites either don't believe that climate change is a serious problem or, if they do, they have decided that their best chance is to work to save themselves, letting the rest of us starve, sink, or boil (I call it the Kiribati Effect). Then, for many industrial lobbies, acting against climate change means losing money. In all cases, the logical strategy for them is to ignore the problem - at least in public. And the government is simply using techniques it knows how to use and that has used in the past.

It is not even so difficult to deceive the public on climate change. We are all subjected to "doomsday fatigue" and most people just can't seem to be able to keep their attention on something that changes slowly over the years. And we are all sensible to deception by omission. The result of the combined action of the government and of this common attitude is a "palpable ratings killer" for all the news regarding climate change. I hate to cite the abominable blog by Anthony Watts, but he has been correctly noting the same trend. And even Watts' anti-science blog has been hit by deception by omission! It is a steamroller of propaganda that squeezes away from the debate everything that deals with climate change.

So, we may well be seeing an epochal shift in the public perception of climate change. The end of the world will become old news, as noted by David Wallace-West. Any hope to avoid that? Not easy: it is a nearly impossible battle to be fought against the combined forces of the government, the industrial lobbies, and of the public's apathy. At the very least, we should realize that there is the serious risk of losing it. That is, we may be facing a future in which the very concept of "climate science" will become everyone's laughingstock (do you remember what happened to "The Limits to Growth"?). It will be an epochal defeat for science.

Certainly, the denial of climate change is taking place against a background of increasing temperatures and the associated climate disasters -- events that would seem to be difficult to ignore. But, in practice, they are ignored. What would we need to push people out of their apathy? Giant fires? We are having them. Scorching heatwaves? Here you go. Droughts? Sure. None of these events are having an impact on the public's views on climate. Imagine that, in a few years, we will see the Arctic Ocean free of ice in Summer. Can you imagine the reaction? Something like: "Ho-hum, yes, so what? The Arctic Ocean was free from ice millions of years ago. Climate changes all the time, you know?"

We are playing, it seems, with a doomsday version of the story of Goldilocks and the three bears. A climate catastrophe that's too small will not have any effect on people's views, but if it is too big it will be too late to avoid a disastrous Seneca Cliff for the whole human civilization. We would need a catastrophe just big enough -- but it is at least unlikely that the Earth's climate will nicely provide us with it.

At the very least, we should recognize that we have been doing something wrong in terms of managing the public perception of climate change. Then, we need some kind of "plan B". Any suggestions?

Note added after publication: clearly, I am not the only one noticing this downward trend (the only people totally missing it seem to be those pompous climate scientists). Two examples

"Climate Change has Run its Course" by Tyler Durden, citing Steven Hayward (h/t Peter Speight)

"Climate Change is not People's Most Pressing Concern" - Again the usual abominable blog, but they are no fools